RS24: Some Thoughts on Healing From Jesus

A: I’ve read some interesting theories over the years to explain the healing miracles in the Gospels. Some of these theories fall under the “Quest for the Historical Jesus” umbrella. There’s the theory that the miracles stories are reports of true supernatural events — proof of Jesus’ divinity and sovereignty over the powers of evil. (This theory appeals to devout evangelical Christians.) On the other end of the spectrum, there’s the theory that the healing miracles should not be understood as fact but as pure metaphor — as literary window-dressing to enhance the credibility of the main character, Jesus. (This theory appeals to liberal and progressive Christians, who often don’t believe in miracles.)

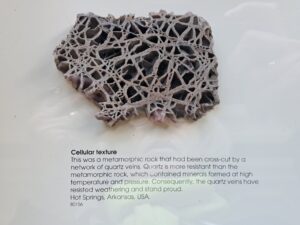

“. . . [Jesus] said to them, ‘Those who are well have no need of a physician, but those who are sick; I have come to call not the righteous but sinners'” (Mark 2:17). Photo credit JAT 2017.

So whatcha say, big guy? Were you wandering around the Galilee as a Jewish magician with serious DSM-IV issues? A wannabe charismatic prophet suffering from a dissociative disorder? A delusional shaman who had a honkin’ big need for an olanzapine prescription? Is this who you really were?

J (chuckling): These guys make me sound like a creepy bad guy from the Criminal Minds series.

A: Yeah, like that two-part episode where James Van Der Beek plays an UnSub who has a multiple personality disorder (Season Two, “The Big Game” and “Revelations.”) One of his “personalities” (the really dangerous one) is an apocalyptic Christian prophet.

J: That’s a good example. A person suffering from a dissociative disorder is not a well person and needs intensive medical care from a team of trained professionals. To suggest that it’s a good idea for a religious teacher or shaman to intentionally induce a state of altered consciousness (“spirit possession”) or a permanent state of dissociation in his/her followers is not only morally reprehensible but is also questionable from a legal point of view.

A: So you didn’t try to teach your followers how to have spontaneous dissociative experiences of being possessed by Spirit?

J (shaking his head): No. I did not. I taught my followers that the key to knowing God is to first know yourself. This is, by definition, the very opposite of dissociative experiences.

A: What about Paul? Did Paul encourage these states of “spirit possession”?

J: Absolutely. He not only encouraged these states, but promoted them as one of the major “drawing cards” of his new religion — buy my Saviour and as an added bonus you’ll receive a free gift from Spirit! Discover how with my easy salvation you can receive, at no additional charge, a special gift of the utterance of wisdom or the utterance of knowledge or faith or gifts of healing or working of miracles or prophecy or discernment of spirits or various kinds of tongues or the gift of interpretation of tongues (one gift per customer, choice made by Spirit at time of purchase, no substitutions, all gifts subject to laws of Divine Cause & Effect, this is a time-limited offer, so call one of our helpful customer service agents now!).

A: It never ceases to amaze me how rarely Paul talks about healing in his letters. Why doesn’t he talk about medical healing — the kind of roll-up-your-sleeves-and-touch-your-neighbour kind of healing you engaged in? Why doesn’t he care?

J: He wasn’t interested in helping people find healing. He had different concerns — occult concerns related to power and order and perfectionism, as we’ve discussed. As far as Paul was concerned, sick people were defective. They’d already proven their imperfection and undesirability in the kingdom of God. Corrupt mortal flesh — sarx in Greek — was an ongoing source of shame and judgment, so who cared? Paul’s focus was the mind and the soul, which were infinitely superior to mere flesh, in his view. To choose to heal flesh, as I did, by starting with the flesh — with the actual physical body instead of the pure Platonic Mind — was an incomprehensible paradigm to Paul. In other words, he thought basic medical science made no sense and was a complete waste of time and divine energy.

A: But that’s what you actually did. You started with the actual physical body, not the pure mind or soul. You helped heal people’s bodies so they could find the courage and strength to build their own relationships with God.

J: Early on in my journey as a practising mystic — not as a dissociated prophet, but as a mentally healthy mystic and channeller — my guardian angel (my daemon in the Greek — not to be confused with the English word “demon”) gave me an excellent analogy. She said this:

“The flowers in the field that you admire, that stop your heart with wonder and beauty, are not like dragon’s teeth sown by Cadmus in the field. You cannot treat them in the ways you’ve been taught. You must think of the flowers in the field as the emotions of God the Mother and God the Father — their memories, their feelings, their stories from times far more ancient than you or any other human being can remember.

The journey through this field of flowers cannot be like the Labours of Heracles if you want to feel the wonder of knowing God. You must tread softly. You must not trample in your haste to get to the other side. You must listen with all your heart and all your mind and all your body and all your soul to the quiet whispers of the lilies.

Each person you meet is like a lily of the field. The roots and the leaves of the lily bear the weight of the colourful blossom, but without the unseen roots and the hard-working leaves, there would be no chance for the lily to produce its harvest.

Treat the body of all you meet in the same way you would treat God’s lilies. Respect all parts of the plant, including the most humble and least attractive parts. Even the smallest root has a part to play. Do not despise the leaves for the sake of the flower’s beauty. The flower fades quickly, but the strongly rooted plant produces blossoms again if it is properly cared for.

Care first for the roots and the humble green plant, and, with time and gentle handling, it will reward you.”

This is why I rejected all religious models about the nature of the human body, and turned to a scientific model with the help of my guardian angels and God. There was a lot I didn’t understand about the inner workings of the human body, but one thing seemed clear to me:

If God made these bodies for us, they must be worth looking after.

_______________________________________________________________________________

Book Review

STEVAN L. DAVIES. JESUS THE HEALER: POSSESSION, TRANCE, AND THE ORIGINS OF CHRISTIANITY. NEW YORK: CONTINUUM, 1995. ISBN 0-8264-0794-3

Review by Jennifer Thomas November 1, 2007

Breathe deeply before you begin to read Stevan Davies book Jesus the Healer. There’s no index, no table of contents, no glossary, no illustrations or diagrams, not even an introduction to orient you in this book, so if you lose the thread of Davies’s argument, you have to retrace your steps. This isn’t a book where you can jump in at any point and quickly grasp the author’s argument. Davies’s thesis is quite complex, and he keeps adding to it chapter by chapter as he attempts (in his own words) to “bring closer together the two continents of Jesus research: historical scholarship and theological reflection” (p.18). On the plus side, the book is a mere 216 pages long, including its 7-page bibliography.

One puzzling aspect of this 1995 book is the lack of biographical information about the author. We’re told nothing about his education or background. Is he a professional journalist or is he a member of academia? We don’t know. All we know is that he’s the author of three other books. A search of my own bookshelves produced a copy of The Gospel of Thomas (2002), translated and annotated by Stevan Davies, Professor of Religious Studies at College Misericordia in Pennsylvania. An internet search yielded the same information. So we can rest assured that he deserves our attention.

Davies begins his book with a brief overview of research into the historical Jesus over the last hundred years. Rejecting the prevailing view of Jesus as some form of teacher, Davies tackles the less well examined paradigm of Jesus as healer. His approach is secular, not theological. For him, New Testament reports of supernatural occurrences are a goldmine of anthropological and psychological data that other researchers have wrongly ignored. He sets out to show us how we might reexamine the passages about exorcisms, healings, and the Son of God, and reinterpret them in light of 20th century theories about “spirit-possession” and “demon-possession.”

Chapter 2 summarizes the anthropological and psychological models Davies relies on to categorize possession: the state wherein a person’s normal persona is believed to be displaced by a “possessing” spirit or demon. Davies is very clear that it’s the belief that’s important. The belief makes it somehow “real” to the people experiencing it. And this in turn makes it an “historical event.” In other words, researchers of the historical Jesus can use biblical passages about exorcism without fear that they’re endorsing the paranormal. This part of Davies’s thesis may prove to have more lasting value to the field than some of his other conclusions.

In Chapter 3, Davies briefly examines descriptions of 1st century Jewish prophets in Josephus, Philo of Alexandria, and the New Testament. From here, he leads into the baptism of Jesus, which he asserts is the correct starting place for understanding Jesus. Davies uses spirit-possession theory to suggest that John’s baptism triggered a spontaneous dissociative experience in Jesus that led Jesus (and others) to believe he was possessed by the spirit of God.

Building on this novel approach, Davies looks at questions about Jesus’ healings (Chapter 5); demon possession (Chapter 6); Jesus’ exorcisms (Chapter 7); and Jesus and his associates (Chapter 8). But all of these chapters are really a prelude to Chapters 9 and 10, where Davies tells us that Jesus induced in his followers an altered state of consciousness (ASC) called the “kingdom of God.” The paradoxical nature of some of Jesus’ parables and sayings is proof to Davies that Jesus was using a healing method akin to the hypnotherapy techniques of American psychotherapist Milton Erickson.

In the last section of the book (Chapters 11 to 13), Davies, not content with a basic model for how Jesus might have healed others, tries to expand his thesis to explain to modern readers why the Johannine-style sayings attributed to Jesus should be considered just as historically authentic as synoptic-style sayings; why we should view early Christianity as a “missionary spirit-possession cult”; and why we must conclude that both Paul and John used “inductive discourse” (that is, intentionally confusing speech) to generate a spontaneous experience of spirit-possession in potential converts.

By the time I finished reading the book, I had found several inconsistencies in his argument, two or three outright contradictions, and an instance where the statistical figures he quoted did not add up (quite literally). Likely these were unintentional errors. And I can look past them. What I can’t look past is Davies’s preposterous theory that the authors of Q and the synoptics recorded only the sayings of Jesus when he was speaking in his own voice as Jesus, and that the author of John wrote down only the sayings of Jesus when he was “possessed” by the Spirit of God (Chapter 11). And that’s two different people, so of course the sayings sound different!

My ultimate impression? I couldn’t escape the sense that Davies had gleefully picked fruit from the tree of knowledge in anthropology and psychology, and had tried to put it in a nice, neat gift basket he could present to other New Testament scholars as a sort of sublime “theory of everything.” Unfortunately, he didn’t know when to stop filling the basket. He damaged his own thesis because he failed to grasp its limits. So I would advise caution in relying on the material in this book.

Jesus the Healer is not currently in print.