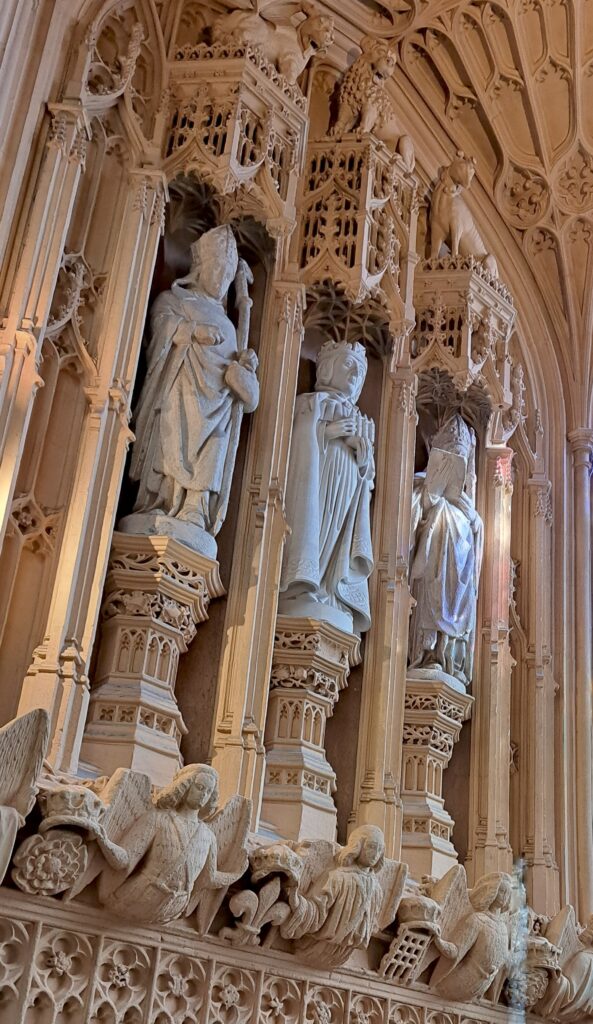

The James Ossuary. Photo by Paradiso (English Wikipedia, via Wikipedia Commons). The James ossuary was on display at the Royal Ontario Museum from Nov. 15, 2002 to Jan. 5, 2003.

In honour of today’s press release today from the Biblical Archaeology Review, with its hot-off-the-press link to Hershel Shanks’ article about the James Ossuary — “‘Brother of Jesus’ Inscription is Authentic!” (note: the Biblical Archaeology Society subsequently removed this article from its website) — I’m posting a term paper I wrote for an Historical Jesus course as a graduate student in theological studies.

I call the essay “Excavating James.” I’ve posted it here as I wrote it in December 2007, several years before an Israeli court found antiquities collector Oded Golan and antiquities dealer Robert Deutsch not guilty of forgery charges after a five year trial.* In my view, the defendants in this forgery trial ably demonstrated how scientific research can be used with dignity, appropriateness, and courage to push back against the vested interests of entrenched dogmatic beliefs.

I should also note that my Masters degree in Art Conservation (Artifact stream) offered me insights into the chemistry raised in this paper.

_________________

EXCAVATING JAMES:

BREAKING THROUGH OLD ASSUMPTIONS

by Jennifer Thomas

December 14, 2007

In October 2002, an unprovenanced chalk ossuary with probable origins in first century Jerusalem made international headlines when a press conference highlighted the possible significance of the box’s Aramaic inscription: “Ya’aquov bar Yosef akhui diYeshua,” translated as “Jacob, son of Joseph, brother of Jesus” (Shanks and Witherington 22). The ossuary, commonly known as the James Ossuary, ignited a firestorm of controversy which has not yet subsided. The scholarly debate over the inscription’s authenticity has been complicated by several factors, including its acquisition by Tel Aviv collector Oded Golan; the puzzling evidence of its having been cleaned more than once (Krumbein, “Findings: Ossuary” par. 2); its history of repair by Royal Ontario Museum conservators after it sustained damage during shipping (Shanks and Witherington 36-40); its focus in the forgery charges brought by Israeli police against Golan; its examination by Israeli police and by independent geomicrobiologist Wolfgang Krumbein, hired by Golan’s defence attorney; and its recent inclusion by filmmaker Simcha Jacobovici and paleobiologist Charles Pellegrino among the Talpiot Tomb ossuaries in their 2007 book, The Jesus Family Tomb. Some of the data presented by Jacobovici and Pellegrino is intriguing and worthy of more study. If further research can confirm the tentative scientifically established link between the James Ossuary and the Talpiot Tomb, then biblical scholars may be forced to reexamine some of their assumptions about the historical Jesus. In particular, the frequently ignored Epistle of James, when read against the background of the Talpiot Tomb and its ossuaries, in the manner of Crossan and Reed, may prove to have greater value as an exegetical tool for understanding Jesus than has previously been envisioned.

When John Crossan and Jonathan Reed revised their book Excavating Jesus to place the James Ossuary in the number one spot of their top ten archaeological discoveries related to Jesus, they probably never imagined that less than five years later a Toronto filmmaker would start knocking on doors in a Jerusalem suburb and asking residents if they had a tomb in their basement. The tomb in question was the Tomb of Ten Ossuaries, found accidentally in East Talpiot in 1980 while contractors were levelling ground for new construction. The Department of Antiquities (later called the Israel Antiquities Authority, or IAA) was contacted, and IAA archaeologists were dispatched to perform salvage archeology. The team physically entered the tomb, mapped the antechamber and the lower chamber with its six niches or kokhim, noted that almost a metre of terra rossa covered the floor of the lower chamber, and removed all the contents, including the red soil. The tomb’s ossuaries – at least, the nine that were later fully catalogued of the ten that were documented on-site – were taken to an IAA warehouse. The tomb itself was generally believed to have been filled with concrete in 1980 during construction of a condominium complex. Certainly this is Crossan and Reed’s stated belief (19). As we shall, however, rumours of the tomb’s demise were greatly exaggerated.

Amos Kloner, of the original IAA team, did not publish the group’s findings until 1996. Apparently, few scholars knew before then that six of the nine Talpiot ossuaries in the IAA’s possession were inscribed with names familiar to readers of the Gospels (an unusually high inscription rate, when compared to other ossuaries catalogued by the IAA (Shanks and Witherington 12)). In 1996, a BBC film crew came across the cluster of inscribed ossuaries, and created a brief media stir with their story (Jacobovici and Pellegrino 23). It is important, however, to separate media sensation from the fact of the tomb’s authenticity. Crossan and Reed quote from a 1996 article in which Joe Zias, then curator of the IAA, said, “[the list of names from the ossuaries] came from a very good, undisturbed, archaeological context. It was found by archaeologists, read by them, interpreted by them . . . a very, very good text” (19). The descriptions of the ten Talpiot Tomb ossuaries (nine in the possession of the IAA and one missing) are shown in Table 1.

Summary of Talpiot Tomb ossuary inscriptions (c) JAT 2007:

What are we to do with this list of family names that includes a Mary, a Jude (son of Jesus), a Matthew, a Jesus (son of Joseph), a Joseph, and a second Mary? Researchers tells us that Mary was a common name for daughters in the Second Temple period (Pfann 8). Shanks and Witherington, citing Rachel Hachlili, report that from the 1st century BCE to the 1st century CE, Joseph was second in popularity only to Simon, Judah was third, Jesus was sixth, Matthew was eighth, and Jacob/James was thirteenth among 18 Jewish male names that appear frequently in the archaeological record (56). In themselves, the inscriptions on the Talpiot ossuaries are not remarkable if they are viewed independently of each other. But they are not independent. They are a group, and must be examined as a group. They were found together. They were found in a South Jerusalem family tomb that, because of its size, location, and quality of workmanship, could only have been built by someone of means.

Pellegrino says in his book that Jacobovici took the list of six names to Andrey Feuerverger, a University of Toronto statistician (111-114). Feuerverger calculated a conservative “P factor” (probability factor) “of 600 to one in favor of the tomb belonging to the family of Jesus of Nazareth” (114). Another way to put this is to say “one in 600 families (on the conservative side) would have that particular combination of names purely by chance, based on the distribution of individual names in the population” (Mims, “Special Report” 1, quoting �TABLE 1: SUMMARY OF INSCRIPTION DATA FROM TEN OSSUARIES FOUND IN TALPIOT TOMB).

In an interview with Christopher Mims published by Scientific American in March 2007, Feuerverger says, “I did permit the number one in 600 to be used in the film. I’m prepared to stand behind that but on the understanding that these numbers were calculated based on the assumptions that I was asked to use . . . I’m not a biblical scholar” (“Q&A” 2). One of the assumptions is that the family could afford an ossuarial burial.

The P factor would rise if it could be established, as Jacobovici and Pellegrino assert, that the James Ossuary is the missing tenth ossuary from the Talpiot Tomb. This may not be as far-fetched as it seems. Pellegrino worked with Bob Genna, director of the Suffolk County Crime Lab in New York, to investigate the possibility of using “patina fingerprinting” to scientifically establish provenance. Pellegrino says this:

My idea about patina fingerprinting rests on the fact that each soil type and rock matrix possesses its own private spectrum of magnesium, titanium, and other trace elements.

In theory, the patina inside a tomb or on the surfaces of its artifacts should develop its own chemically distinct signature, depending on a constellation of variable conditions, including the minerals and bacterial populations present at any specific location and the quantities of water moving through that specific “constellation.”

If such a chemical “fingerprint” existed, scanning patina samples on a quantum level with an electron microprobe would reveal a chemical spectrum that could be matched to a specific tomb and to any objects that come from it. (176)

His proposal is gutsy but by no means ludicrous or impossible from the perspective of analytical chemistry and related fields. At the least, it deserves further consideration. Publication in a peer-reviewed journal would assist others in assessing its feasibility. At the moment, though, we have Pellegrino’s anecdotal findings, some of which are published in the form of four spectra in the colour plate section of the book. He and Genna took patina samples from the following sources: the Jesus, Mariamne, and Matthew ossuaries from the Talpiot tomb, the tomb itself, the James ossuary, and a number of provenanced ossuaries from tombs known to have similar conditions to the Talpiot tomb. His proposed method relied entirely on the availability of patina samples from the walls of the Tomb of Ten Ossuaries. Had the tomb been filled with concrete, as some had been led to believe, it would have been impossible to retrieve an uncontaminated sample. Fortunately – and for this we must thank renegade explorer Jacobovici and his associates, who wouldn’t take no for an answer – the tomb was “rediscovered” in 2005. It lay beneath a concrete and steel slab on a terrace between two condominium buildings. A tenant who had lived in one of the buildings since the beginning told Jacobovici’s team that archaeologists had left the tomb open, but tenants had built the slab on top to keep children out (150). In addition, religious authorities had turned the tomb into a genizah, or burial chamber for damaged holy texts, before it was sealed (153). The tomb was now carpeted with fragments of holy books. There was concern that the presence of the decomposing texts might have significantly altered the chemical composition of the tomb’s patina over the previous 25 years; however, this was not borne out by the microprobe studies (180).

When Pellegrino and Genna used an electron microscope to examine a patina sample from the James ossuary, provided by the Israel Geological Study, they saw “hundreds of tiny fiber fragments” on the sample (184). They concluded that “someone in modern times had given the James ossuary a hard scrubbing with a piece of cloth . . . .(184)” They directed the electron microprobe to the fibres themselves, and got large chlorine and phosphorus peaks. “This was consistent with the phosphate-spiked detergents that were in common use during the 1970s and early 1980s” (184). Someone had apparently cleaned the James ossuary with a cloth soaked in a chlorine- and phosphate- based detergent.

Probes of the James ossuary patina clearly revealed the same detergent contaminants. When these modern contaminants were factored out, the remaining spectrum was identical to those obtained from the Talpiot tomb walls and from the Jesus, Mariamne, and Matthew ossuaries (185). Further, five probes taken of a James patina sample provided by the Royal Ontario Museum were also identical, “right down to contamination by cloth fibers and phosphate-based detergent” (185).

Meanwhile, the electron microprobe studies of samples taken from unrelated Israeli ossuaries yielded spectra that were significantly different from each other and from the Talpiot cluster, even when patina samples were visually indistinguishable from the Talpiot patina under light microscopy. Pellegrino says, “In conclusion, it seemed that, compared to other patina samples from ossuaries found in the Jerusalem environment, the Talpiot tomb ossuaries exhibited a patina fingerprint or profile that matched the James ossuary and no other” (188).

If we were to rely solely on Pellegrino’s admittedly novel technique to “rehabilitate” the James ossuary’s historical significance, we would not have much. However, because the box and samples from the box have been studied so many times since 2002 by specialists from different disciplines, including epigraphers, geochemists, archaeologists, art conservators, and even a geomicrobiologist, we have considerable scientific data at our disposal.

In June 2003, the IAA issued a public statement declaring the inscription on the James ossuary a modern-day forgery. Two of the 14 Israeli scholars who were invited to prepare an authenticity report were Avner Ayalon of the Geological Survey of Israel and Yuval Goren of Tel Aviv University’s Department of Archaeology (Fitzmyer 3). These two, together with Miryam Bar-Matthews, also of the Geological Survey, examined the James ossuary, and published their findings in the Journal of Archaeological Science (Ayalon et al). They, too, chose a method never before used to assess the authenticity of archaeological artifacts. They took patina samples from various parts of the inscription, from other surface areas of the James ossuary, and from the surface patina and letters patina of unrelated Jerusalem ossuaries; ground the samples; used a mass spectrometer to analyse the oxygen isotopic composition (δ18O values) of each sample; then compared the results to well-dated secondary calcite (speleotherms) deposited in Jerusalem area caves during the last 3,000 years. Since only one James letter sample (of seven) fell within the same range as the other types of samples, Ayalon et al concluded the patina of the inscription could not have been formed “in the natural conditions that prevailed in the Judean Mountains during the last 3000 years, [indicating] that the patina covering the letters was artificially prepared, most probably with hot water, and deposited onto the underlying letters” (1188).

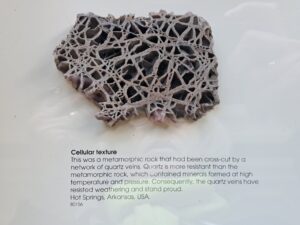

There are several problems with this paper, two of which are noted here. First, although Ayalon et al acknowledge that the inscription had been observed in a previous study to be freshly cleaned, they do not discuss how the residue of earlier cleaning might affect δ18O values. This is a significant lapse. Second, they apparently base the suitability of their δ18O method on the assumption that the patina on the rest of the James ossuary was pure calcite formed in a typical Judean cave environment, that is, in an enclosed or semi-enclosed atmosphere absent of soil. Krumbein’s report, however, conclusively demonstrates that the patina is not pure calcite, and that the presence of apatite, whewellite, weddelite, and quartz in the patina, along with biopitting and plant traces, suggests that “the cave in which the James ossuary was placed, either collapsed centuries earlier, or alluvial deposits penetrated the chamber together with water and buried the ossuary, either completely or partially . . .[rendering] δ18O isotopic tests irrelevant” (under “Findings: Ossuary”; italics added).

When Krumbein examined the ossuary, along with two other disputed artifacts, in Jerusalem in 2005, the Talpiot tomb, with its verified accumulation of terra rossa, had not yet entered the picture as the possible original resting place for the unprovenanced James ossuary. Nonetheless, his thorough examination and reported findings are fully in agreement with the documented conditions in which ten ossuaries were originally found in 1980.

It is by no means certain, based on the scientific evidence, that the inscription on the James ossuary is a modern forgery (for a current example of the ongoing debate, see the BAR 33.6 article). The box itself, however, seems genuine (Ayalon et al 1185). Are there other explanations for the “Jacob, son of Joseph, brother of Jesus” inscription? Of course. It is possible the inscription is a well-meaning ancient addition to a plain box. It is also possible the latter part of the inscription (“brother of Jesus”) was added recently to an authentic “James, son of Joseph” inscription, as some have argued (for example, Chadwick as cited by Shanks and Witherington 42). The inscription might even be an ancient forgery. On the other hand, the entire inscription could be authentic. The question for historical Jesus researchers is this: If the ossuary and its inscription are authentic, what does it say about Jesus? Can we stretch the question further to ask what it might mean if the James ossuary is the missing tenth Talpiot bone box? Crossan and Reed have said, with regard to the James ossuary, that “like [the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Nag Hammadi Codices], the ossuary is now here and its presence demands discussion. . . . It is one single artifact that brings together archaeology and exegesis. It is also one single artifact that emphasizes how such objects are of value only when embedded among all those other discoveries that give it full context and final meaning” (28). I would argue that the Talpiot tomb findings create important archeological, scientific, and exegetical context, and that the James ossuary should be examined further in light of that context.

We can say with some measure of confidence that in the period during which ossuarial burial was practised in Jerusalem (usually given as 20 BCE to 70 CE (Shanks and Witherington 69)) a family who counted among their members a Mary, a Jude, a Matthew, a Jesus, a Joseph, another Mary, and possibly a James, had enough wealth and prestige to build a spacious tomb in the bedrock of a hill just south of the old city. Different languages were used on the ossuary inscriptions: Hebrew and Aramaic, but also Greek, with one name (Maria) a Latin version of its Aramaic counterpart. From this evidence, it could be argued the family was familiar with and possibly part of the wider Greco-Roman culture of 1st century Palestine. The family also had a penchant for widely popular names, and possibly followed a custom of naming children after close relatives.

We know from exegetical evidence that Jesus of Nazareth had a brother named Jacob or James. The Gospels of Matthew and Mark both name Jesus as the son of Mary and the brother of James, Joseph, Judas, and Simon (Mt 13:55; Mk 6:3), though Jesus’ two sisters are not named in these passages. Matthew and Mark also refer to a Mary who is mother of James and Joseph (Mt 27:56; Mk 15:40). Although it is not clear which Mary is being referred to in these latter verses, she could be Mary the mother of Jesus, in which case James and Joseph would again be named brothers of Jesus. So we have two independent Synoptic sources, Matthew and Mark, that specifically name James. The Gospel of Thomas, which is considered an independent source by some (Crossan and Reed 9), refers to James the Just in Saying 12. Further, James appears a number of times in Acts and the writings of Paul. Paul lists James among those who have seen the risen Christ (1 Cor 15:7), and when Paul is writing his letter to Galatians, he describes James as one of the “pillars” of the Jerusalem church (Gal 2:9). The much-overlooked Epistle of James purports to be written by “James, a servant of God and of the Lord Jesus Christ” (Jas 1:1). We also have extra-canonical sources that name James, two of which report on his death in Jerusalem a few years before the destruction of the city in 70 CE (Gillman 621). Josephus reports that James was stoned in 62 CE on the orders of high priest Ananus (Ant 20:200). Hegesippus, writing ca. 180 and quoted by Eusebius in the 4th century, gives a dramatic account of James’s martyrdom in 67 CE (?) at the hands of the scribes and Pharisees. Also from Hegesippus through Eusebius, we learn that “James became the first bishop of Jerusalem in part because he was the brother of Jesus” (Shanks and Witherington 96).

One begins to wonder why a man from the small peasant town of Nazareth in rural Galilee, where families “had an interest in keeping the head count low” (Hanson and Oakman 58) and the total population was probably less than 400 people (Reed 131), had such a large number of presumably adult siblings when childhood death rates were so high, and why one sibling – James – had such a position of honour and authority in Jerusalem. Archaeological excavations in Nazareth have brought to light no public structures and no public inscriptions from the Early Roman Period, which attests to “the level of illiteracy and lack of elite sponsors” there (Reed 131). Juxtaposed against this archaeological evidence, we have not one but two men from the same generation of the same family who rose, in the midst of an honour-shame culture, from the humblest of origins to positions of great moral authority. Both men knew Jerusalem and died there. Both had friends there. Both surely possessed impressive oratorical skills, otherwise they would have been ignored. Surely these two men started out with more than the knowledge of how to press Nazareth’s grapes into wine (see evidence for a vineyard and wine pressing vat: Reed 132). Something does not fit with a popular understanding of the historical Jesus as an illiterate Galilean peasant carpenter wisdom sage (for example Crossan and Reed; Mack). We might understand Jesus by himself in this way. But by all accounts, Jesus had a family. We must try to place Jesus more solidly within his large family, and within a culture that lived and breathed for status.

In 2 Corinthians, Paul engages in a lengthy appeal for monetary contributions to the Jerusalem church (“the collection”) (2 Cor 8:1 – 9:15). In the course of his letter, he says, “For you know the generous act [or the grace] of our Lord Jesus Christ, that though he was rich, yet for your sakes he became poor, so that by his poverty you might become rich” (2 Cor 8:9). In the Greek, Paul uses ἐπτώχευσεν πλούσιος, “the well-to-do man became poor.” This verse is usually interpreted as being metaphorical, more akin to the christological construction in Philippians 2:6-8 (footnotes in Coogan NT 302). But maybe Paul isn’t being metaphorical at all. Maybe he means exactly what he says: that Jesus intentionally gave up his wealth to do God’s work. Paul, by his own admission, visited Jerusalem and saw James the Lord’s brother (Gal 1:18-19). If Paul had not known anything about Jesus’ family before this visit, he certainly did afterwards. Did Paul learn that Jesus had come from a privileged family with strong ties to Jerusalem? How would such knowledge have affected Paul’s understanding of his own divinely appointed mission, the mission he describes in Galatians 1:15-17? Would it have been to Paul’s advantage or disadvantage that the man who spoke so clearly to the non-elite about the spiritual woes of being rich (eg. Lk 6:24) might himself have originated in a family of wealth and status?

A modern analogy might be of help in understanding the historical Jesus not as a man who came from the bottom up, but as man who had the courage to intentionally step off the upper part of the pyramid, and live as a person among persons. Imagine, for the sake of argument, that one of the many descendants of American oligarch Joseph Kennedy suddenly had a profound religious experience, and saw for the first time how much suffering had been caused by his family’s commitment to certain values. What if this descendent renounced his family’s elitist way of life, moved to Canada, got a regular job, and used his spare time to study scripture? His family probably wouldn’t like him very much. They might even lie to their friends about where he had gone, rather than face the embarrassment of being “disowned” by him on spiritual grounds. Of course, such lies would become harder to maintain if he became known in his own right as a brilliant spiritual teacher up there in the boonies, a teacher of social and gender equality and . . . what’s that? . . . miraculous healings from God? For this we gave him an education? The shame, the shame.

Eventually, of course, word would get up to Canada that the guy working over there on that construction site is a Kennedy – one of those Kennedys. And suddenly the people who had ignored him the day before would invite him over to dinner to talk about his favourite subject, God. Even the local bishop might not be immune to the cachet of this gentleman’s esteemed lineage. Doors have a way of opening for those who come from “the right sort of people.”

Two thousand years ago, Jesus went through a lot of different doors. Many of those doors were owned by priests, Pharisees, scribes, and other elites who wouldn’t have been caught dead talking to a Galilean peasant on the street, let alone seek him out for questioning in public places (Mt 22:15-46; Mk 11:27-33; Lk 20:1-8) or invite him to dinner (Lk 14:1-24). However, it is quite believable that they would talk to a man who had “ascribed honour” on the basis of his descent (Hanson and Oakman 26-31), even if they didn’t agree with his theology. Much has been made of the evidence that Jesus ate with “sinners” and “tax collectors” and other outcasts. But it is just important that Jesus was known to dine with the elite. One could say that, in his ministry, Jesus swung both ways. This may be what made Jesus unique and loved by so many.

Whatever else can be said of Jesus, no one can dispute his commitment to God. He was a man of deep faith. He strove to communicate to the people around him the depth of God’s love for them. To this end, it was probably important to Jesus that he have the chance to speak in person to as many people as possible. He was not one to retire to life in an ascetic religious community like the one at Qumran. He was walking and talking (and dining) right up until his arrest. So, from a purely practical point of view, it would have been shrewd of Jesus to avoid talking about his family lineage, whatever its exact nature. The last time a devout Jewish family claiming priestly legitimacy had gathered political support from the Jewish rank and file, a rebellion had erupted that swept the Seleucid rulers from the ancient kingdoms of Judah and Israel. The Maccabean revolt, which proved the power of priestly Jewish bloodlines, would not have been forgotten by Palestine’s new Roman rulers. Here was a clear case of discretion being the better part of valour.

Many who would argue with the thesis presented here might wonder why an educated man from a privileged family would not have written down some of his own teachings. Surely such a man would be literate! Where are the letters of Jesus? Why did he not put something down on papyrus, and hand it to a trusted friend or family member?

Well, maybe he did. Maybe his words have been staring at us all along, hidden in plain sight in the canon as part of the Epistle of James.

The Epistle of James has to be one of the least examined sources in the New Testament. Open up the back of books written by historical Jesus researchers and examine the “Ancient Sources Index.” Under James, you will frequently find nothing. Nothing at all – this despite the fact that some of the most sophisticated theology of the New Testament is found in James, and despite the fact that it has obvious links to the Q source (Hartin; Johnson; Wachob). Some might lay the blame at the foot of Luther, who famously decried James as “an epistle of straw” (Laws 622). It seems generally to be avoided in research because its Greek is deemed too elegant for the family of a Galilean artisan (but what of a highly ranked family?); there are only two brief references to Jesus (would Jesus himself brag?); and its discussion of faith and works does not refer specifically to “works of the law” (Law 622) (is that the real message of this epistle?). On the basis of these arguments, some declare it pseudonymous. In terms of date, it has been placed in the second generation, or even in the 2nd century. However, there is much evidence to support an earlier, first generation date for the epistle of James.

Luke Timothy Johnson has done considerable research in this regard. In his book Brother of Jesus, Friend of God, he says:

With the exception of the evidence in Paul, Acts, and Josephus, the letter is the historically most certain evidence we have concerning James. Even if it is supposed that a composition by James of Jerusalem was later redacted by someone else, the present letter is almost certainly appropriated by early-second-century Christian writings [1 Clement and Shepherd of Hermas]. In fact, there are strong reasons for arguing that the extant letter was composed by James of Jerusalem, whom Paul designates as “brother of the Lord.” What is more, the evidence provided by the letter fits comfortably within that provided by our other earliest and best sources (Paul, Acts, Josephus), whereas it fits only awkwardly if at all within the framework of the later and legendary sources that are used for most reconstructions [here Johnson refers to Witherington in Brother of Jesus]. (2-3)

If Johnson is correct in his conclusions, then the Epistle of James, or parts of that epistle, could well be another independent source for understanding the historical Jesus (though Johnson himself would no doubt be chagrined at seeing his work used to support a theory he does not subscribe to (Kirby 10)).

The letter of James, far from being an epistle of straw, concerns itself with teaching the difference between earthly wisdom that does not come from above versus the wisdom that does come from above, and is “first pure, then peaceable, gentle, willing to yield, full of mercy and good fruits, without a trace of partiality or hypocrisy” (3:17). This is an extraordinary vision of God, one that is in stark contrast to the God who clearly plays favourites in various Old Testament and apocryphal texts. Another breathtaking vision of God is given in Chapter 1, where the author says, “No one, when tempted, should say, ‘I am being tempted by God’; for God cannot be tempted by evil and he himself tempts no one. But one is tempted by one’s own desire, being lured and enticed by it” (1:13-14). He then goes on to say that “every generous act of giving, with every perfect gift, is from above, coming down from the Father of lights, with whom there is no variation or shadow due to change” (1:17). Note the complete absence of eschatological promises or apocalyptic warnings. The author of these sections, whom I believe was Jesus, is telling readers to take responsibility for their own actions and not blame their bad choices on a God who has “tempted them.” He is also saying they should not fear change, because God’s love never changes even when other things do.

When we place this understanding against the epistle’s opening statements – “My brothers and sisters, whenever you face trials of any kind, consider it nothing but joy, because you know that the testing of your faith produces endurance; and let endurance have its full effect, so that you may be mature and complete, lacking in nothing” (1:2-4) – we can perhaps understand why its message has been so long ignored: this is not a message about justification by works alone, nor is it a message about justification by faith alone. It is an altogether radically new message about asking for God’s help in the here and now in the difficult spiritual task of transforming pain and suffering into maturity, wisdom, and love for one’s neighbour and one’s God, not to earn salvation, but simply because it’s the right thing to do.

No wonder they crucified the guy.

In conclusion, it is possible to apply Crossan’s and Reed’s “Excavating Jesus” method (balancing archeology with exegesis) to the task of “excavating James.” The excavated James can, in turn, shed greater light on the historical Jesus. Recent findings from the Talpiot tomb, the James ossuary, and the Epistle of James cannot be ignored. As a group, they demand discussion. As a group, they have a story to tell us about Jesus. And perhaps Jesus himself still has something to say.

* September 2, 2015: I have two updates to report which are relevant to the material posted on this page:

(1) I’m posting a link to a 2015 documentary that premiered on March 16, 2015 on VisionTV. The documentary, produced by Simcha Jacobovici, and Felix Golubev is called Biblical Conspiracies 6: The James Revelation. In this documentary, Simcha adds to his previous work on possible links between the James ossuary and the Talpiot Tomb ossuaries. He now states that the James ossuary may be a missing eleventh ossuary from the Talpiot Tomb. (His original position was that the James ossuary was the missing tenth ossuary, which mysteriously disappeared in 1980 after the Department of Antiquities (now the IAA) excavated and catalogued the contents of the tomb.) His new position no doubt derives from evidence presented during Oded Golan’s forgery trial which proved that he (Golan) was already in possession of the James ossuary a few years before the Talpiot Tomb was discovered. It’s still possible, however, that the James ossuary was looted at an earlier time from the Talpiot Tomb, as IAA archaeologist Shimon Gibson believes the tomb may have been broken into more than once before its official discovery (Biblical Conspiracies 6, 31 minutes).

In addition, Simcha uses the 2015 documentary to revisit the previous analytical analysis of the chemical fingerprint of the James ossuary inscription patina in comparison to that of the Talpiot Tomb ossuary patinas. This work was originally led by Dr. Charles Pellegrino (paleo-biologist and forensic archaeologist). In the documentary, Simcha consults with geo-archeologist Dr. Aryeh Shimron, who takes samples not from the inscription patina of the James ossuary but from the underside and inside of the box itself (from beneath the surface patina), then compares these with samples taken from the nine remaining Talpiot Tomb ossuaries as well as samples from random chalk ossuaries. Analysis of the chemical signatures shows strong similarities between the James ossuary and the Talpiot Tomb ossuaries, though, as Oded Golan rightly points out in an April 4, 2015 New York Times interview with Isabel Kershner, this isn’t conclusive proof that the James ossuary originally came from the Talpiot Tomb; the James bone box could have come from another burial cave in the same area and still show a similar chemical fingerprint. Samples would have to be taken from a large number of caves in East Talpiot to further refine the data.

It should be noted that Simcha’s new theory and new analytical data have no bearing on the actual authenticity of the James ossuary and its inscription. Whether or not Simcha is right, the James ossuary remains an important and authentic piece of archaeological evidence that can be legitimately combined with other pieces of evidence in the search for the historical Jesus, as stated above.

(2) I’m posting a link to an article by Hershel Shanks which appears in the Sept./Oct. 2015 issue of Biblical Archaeology Review. The article, called “Predilections: Is the ‘Brother of Jesus’ Inscription a Forgery?” reviews some of the recent debates surrounding the authenticity of the James Ossuary inscription and the forgery trial of Oded Golan. Mr. Shanks emphasizes that Mr. Golan did, indeed, own the James Ossuary before the Talpiot Tomb was found and excavated in a 1980 salvage operation. Mr. Shanks also comments on the recent analysis by Dr. Pieter van der Horst of the IAA committee’s own original report on the James ossuary. Says Shanks, “Van der Horst notes that the IAA ‘appointed almost exclusively committee members who had already expressed outspoken opinions to the effect that the inscription was a forgery.'”

BIBLIOGRAPHY (as it originally appeared in the 2007 research paper)

Ayalon, Avner and Miryam Bar-Matthews and Yuval Goren. “Authenticity Examination of the

Inscription on the Ossuary Attributed to James, Brother of Jesus.” Journal of Archaeological Science 31 (2004): 1185-1189.

Coogan. Michael D., Ed. The New Oxford Annotated Bible: New Revised Standard Version with

the Apocrypha, College Edition. 3rd Ed. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2001.

Crossan, John Dominic and Jonathan L. Reed. Excavating Jesus: Beneath the Stones, Behind

the Texts. Rev. and Updated Ed. New York: HarperCollins and HarperSanFrancisco, 2001.

“Demythologizing the Talpiot Tomb: family unit, group No. 1.” Filed under “Lost Tomb of

Jesus.” The View from Jerusalem. May 17, 2007. University of the Holy Land. 04 Dec. 2007 <http://www.uhl.ac/blog//?p=110>.

Fitzmyer, Joseph A. “Update–Finds or Fakes? The James Ossuary and Its Implications.”

Excerpted from Theology Digest 52:4 (2005). Biblical Archaeology Society. Undated. 04 Dec. 2007 <http://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/bswbOOossuary_fitzmyer.asp>.

Gillman, Florence Morgan. “James, Brother of Jesus.” The Anchor Bible Dictionary. Vol. 3.

Ed. David Noel Freedman. New York: Doubleday, 1992. 620-621.

Goren, Yuval. “The Jerusalem Syndrome in Archaeology: Jehoash to James.”

The Bible and Interpretation. Jan. 2004. 04 Dec. 2007 <http://www.bibleinterp.com/articles/Goren_Jerusalem_Syndrome.htm>.

Hanson, K.C. and Douglas E. Oakman. Palestine in the Time of Jesus: Social Structures and

Social Conflicts. Incl. CD-ROM. Minneapolis: Fortress, 1998.

Hartin, Patrick J. James and the Q Sayings of Jesus. Journal for the Study of the New

Testament Supplement Series 47. Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press, 1991.

Jacobovici, Simcha and Charles Pellegrino. The Jesus Family Tomb: The Discovery,

the Investigation, and the Evidence That Could Change History. New York: HarperCollins and HarperSanFrancisco, 2007.

Johnson, Luke Timothy. Brother of Jesus, Friend of God: Studies in the Letter of James.

Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2004.

Kirby, Peter. “Historical Jesus Theories.” Early Christian Writings. 2001-2003. 13 Oct. 2007

<http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/theories.html>.

Krumbein, Wolfgang E. “External Expert Opinion on Three Stone Items.”

Biblical Archaeology Society. Sept. 2005. 04 Dec. 2007 <http://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/bswbOOossuary_Krumbeinreport.pdf>.

Laws, Sophie. “James, Epistle of.” The Anchor Bible Dictionary. Vol. 3. Ed. David Noel

Freedman. New York: Doubleday, 1992. 621-628.

“Leading Scholar Lambastes IAA Committee.” Biblical Archaeology Review 33.6 (2007): 16.

Mack, Burton L. “Q and a Cynic-Like Jesus.” Whose Historical Jesus? Ed. William E. Arnal

and Michel Desjardins. Studies in Christianity and Judaism 7. Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier UP, 1997.

Mims, Christopher. “Q&A With the Statistician Who Calculated the Odds That This Tomb

Belonged to Jesus.” Scientific American. March 2, 2007. 12 Dec. 2007 <http://sciam.com/article.cfm?articleID=13C42878-E7F2-99DF-3B6D16A9656A12FF>.

Mims, Christopher. “Special Report: Has James Cameron Found Jesus’s Tomb or Is It Just

a Statistical Error?” Scientific American. March 2, 2007. 12 Dec. 2007 <http://sciam.com/article.cfm?articleID=14A3C2E6-E7F2-99DF-37A9AEC98FB0702A>.

Pfann, Stephen. “How Do You Solve a Problem Like Maria?” UHL Articles on “The Lost

Tomb of Jesus” Documentary. University of the Holy Land. 2007(?). 11 Dec. 2007 <http://www.uhl.ac/Lost_Tomb/HowDoYouSolveMaria/>.

Reed, Jonathan L. Archaeology and the Galilean Jesus: A Re-examination of the Evidence.

Harrisburg, PA: Trinity, 2000.

Shanks, Hershel and Ben Witherington III. The Brother of Jesus: The Dramatic Story &

Meaning of the First Archaeological Link to Jesus & His Family. New York: HarperCollins and HarperSanFrancisco, 2003.

Wachob, Wesley Hiram. The Voice of Jesus in the Social Rhetoric of James. Society for

New Testament Studies Monograph Series 106. Cambridge, England: Cambridge UP, 2000.

Posted in

Bible,

Favourite Posts,

historical Jesus,

James Ossuary,

Jerusalem Temple,

Jesus' family of origin,

Jesus' original writings,

Letter of James,

Paul vs Jesus,

Realspiritik,

Talpiot Tomb and tagged

James Ossuary,

Talpiot Tomb |